Exhibit Pays Tribute to Life Lost in Creek

Morgantown Dominion Post

8 September 2011

By Lindsey Fleming

The opening reception for “Reflections: Homage to Dunkard Creek”

is set for 6-9 p.m. Friday in the Jackson Kelly Gallery of Arts

Monongahela at 201 High St. For more information on the exhibit,

go to http://web.me.com/paynestake/Homage_to

_Dunkard_Creek/

On a warm, damp summer day two years ago, Anne Payne stood, waders

on, knee-deep in the middle of her friend Wendy’s problem, one the

Mount Morris, Pa., resident had been imploring her to check out

for a while.

“She kept saying, ‘You’ve got to come out. There’s something wrong

with my creek,’ ” Payne said. “I’m like, ‘What am I going to do

about her creek?’ ”

But the Morgantown artist knew, after witnessing the Dunkard Creek

fish kill firsthand, she was going to have to do something.

White carcasses floated somberly downstream. Log jams of the

living, seeking fresh water, were so desperate to reach the tiny

rivulets trickling with it, they suffocated while throwing

themselves on top of one another.

Mudpuppies, “with their little black paws,” crawled up the banks

to escape.

“That was it for me. I could have heard about it ’til the cows

came home, but to stand there and see, it just made you want to

weep.”

Instead of weeping though, Payne decided she must educate herself.

She began attending meetings about the massive kill and its

implications. She researched the more than a 100 species of fish

and mussels officially wiped out due to a toxin in the 2009 golden

algae bloom, as the result of increased levels of total dissolved

solids from mine discharge. And she found out about others — such

as insects, salamanders and frogs — that no one she contacted in

an official capacity confirmed for certain perished. It was the

non-experts, the residents along the creek, who provided her with

lists of those creatures, as well as historical records she

uncovered.

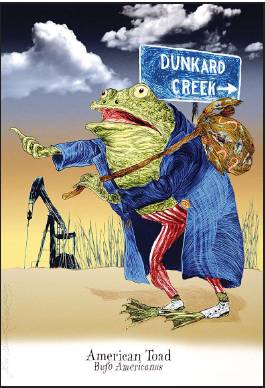

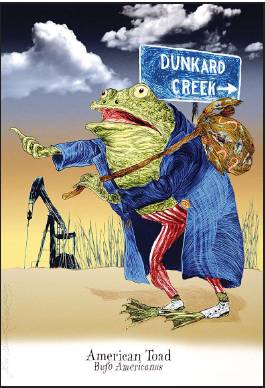

Friday, artwork depicting 90 of those species, created by an equal

number of artists, will adorn the walls of Arts Monongahela during

the opening reception of an exhibit which pays tribute to their

lives. There will also be photos of the creek, information about

the species and the fish kill, an interactive display and a video

of residents along the creek speaking about how the kill affected

them.

The seeds of “Reflections: An Homage to Dunkard Creek” have been

in the works since not long after Payne’s visit to her friend’s

property. It was then when she made the ambitious decision to

paint 116 of the species that were affected. By 2010, she only had

10 pieces completed.

“I’m thinking, I’m 69 years old, let’s do the math here. No, this

is not working,” she said, laughing.

So, when a friend suggested she get someone else to help, she ran

with the idea and decided to randomly assign a species to a number

of fellow artists. Ninety, she said, seemed like a nice round

number.

“I could probably have gotten famous artists from afar who are

activists to participate but I thought, ‘You know, I wanted to be

kind of in a family of artists who have the same physical

connection to the [Monongahela] watershed.’ ”

And that’s when the onslaught of calls began.

She started with Ron Donoughe — a plein air painter she had no

connection with, other than she had seen his work and thought it

would be appropriate. He happily agreed. As did all of the

participants she contacted, which include practicing artists who

live, attended school or have vacationed in the area surrounding

the watershed.

“It’s a big network of people [who are] made of the same water,”

she said of the dozens of artists who hail from Boston, Mass., to

Charleston and many points in between. “We drink it. It falls on

us when it rains. Everybody felt the same connection to this in

varying degrees.”

“In some ways Ann looked at the watershed and saw it as an artshed

too,” said Brent Bailey, director of the Appalachia Program at The

Mountain Institute, a nonprofit organization which sponsors the

exhibit. “This is a whole community of people, [some of whom] have

never even met each other, but are all tied to the same piece of

land. There’s a real heart response here for many of them.”

It’s something Payne realized quickly, during her recruiting

efforts.

“A lot of people, I felt like they almost said, ‘Gee, we’ve been

waiting for your call,’ ” she said.

She said many became acquainted with their assigned species —

which range from algae and large mouth bass to muskies and

Fatmucket Mussels — for the first time. Even those who had

initially expressed concerns about their picks, finding them

boring, ugly or both, came to appreciate them. Some searched the

Web. Others spoke with fishermen and professors to learn more. And

a fair amount traveled to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History

in Pittsburgh to study specimens up close and personal.

The result of such efforts is an abunwork as varied as the species

they represent. Lithographs, prints, watercolors, oils and more,

portray the kaleidescope of colorful life just underneath the

water’s surface and range in tone from whimsical to contemplative.

In an effort to make the traveling exhibit portable,

cost-effective and adaptable to different spaces, Payne required

each artist to create on the same sized surface — a

10-1/4-inch-by-7-inch masonite art board covered with French

watercolor paper.

“It’s something that anybody can do without enormous resources,”

she said. “I made it to go in the back of a car.”

For the next two years, “Reflections” will be on display in

several galleries around the region. And if all goes well, even

farther. The idea is to provide an exhibit that is accessible, so

that anyone inspired by it can welcome it to their community or

easily duplicate it.

This accessibly and the creative spin “Reflections” puts on the

larger environmental issues of water quality and energy use, are

at the crux of why The Mountain Institute partnered with Payne in

its first artistic endeavor, according to Bailey.

The institute, active in West Virginia since 1972, focuses much of

its efforts on environmental education in schools. With

“Reflections” the organization saw a way to reach a broader

audience.

“It’s a really great way to raise awareness,” Bailey said. “This

seemed to be a part of that conversation about energy and water

and how they collide. ... Water is probably the greatest resource

that comes from mountains. And everything springs from the

mountains and we feel like this is just an important resource that

needs to be highlighted.

“And how do you get the public to really take an interest in

something that is so valuable but probably so underappreciated?

Creating this kind of an opportunity for public engagement, to

come and learn and talk about it, seems like a really great way to

further that awareness and that understanding.”

Though the exhibit is intended to spark debate and raise

questions, that’s only a part of what “Reflections” is meant to

inspire in viewers.

“Let’s start with appreciation of what we have. And how we deal

with it will be based on an understanding, an appreciation of

what’s here rather than just looking at numbers and figures,”

Payne said, referring to the fish kill and its future

implications.

She added, “part of that honoring [of the species] isn’t just to

wring our hands and worry. It’s to say, ‘They’re amazing. They’re

marvelous. They’re beautiful. They’re funny. They’re interesting.

They’re useful.’ And at the same time, the humans who created them

are the same way. It’s that interaction. And that’s not about

death. That’s about life.