Old Locks Jam River Traffic

Delays on the Water Hurt Shippers, Push Prices Up as Renovation

Efforts Stall

Wall Street Journal

6 January 2011

By Jennifer Levitz and Cameron McWhirter

BELLE VERNON, Pa.—Barges nearly two football fields long, piled high

with coal, float smoothly down the lower Monongahela River here—until

they reach the 75-year-old Charleroi Locks and Dam, where many get

waylaid at the gate.

The lone functioning lock is set in crumbling concrete. Pieces of steel

hang loose, threatening to gouge barges as they pass. Part of the river

is blocked by construction. For barge operators, Charleroi is a choke

point on the river.

Waterways Locked in a Quandary - Ross Mantle

for The Wall Street Journal

"You can be here for two hours up to 12 hours—that's right out of my

pocket," said Michael Somales, general manager of river operations for

Consol Energy Inc., a Pennsylvania company that carries coal from

Appalachia downriver to power plants along the Ohio River Valley.

In 1994, when the Army Corps of Engineers started a project to replace

two aging locks at Charleroi, completion was expected by 2004. Now, the

work is estimated to drag on until 2023, according to the Corps, which

blames insufficient funding and design complications.

The problems at this aging and deteriorating lock some 30 miles

southeast of Pittsburgh are typical of much of the nation's waterway

infrastructure, which hampers U.S. shippers and the economy as a whole.

The Obama administration, promoting water transport as a cheaper and

energy-saving alternative to trucks and rail, issued $68.2 million in

grants in fiscal 2010 to ports and local governments to buy barges and

build infrastructure to move cargo by water. But the Corps, which

maintains 12,000 miles of waterways and 241 locks that move one-sixth

of the nation's freight, says 54% of those locks are 50 years old or

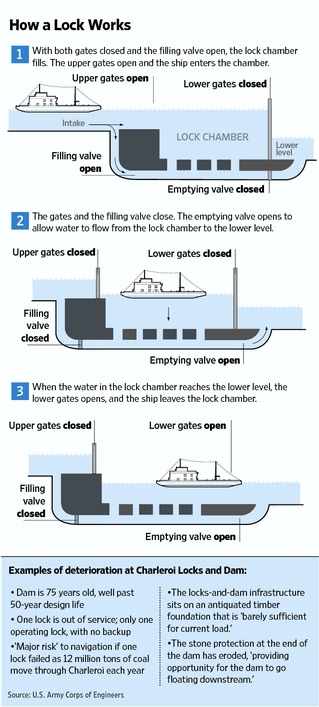

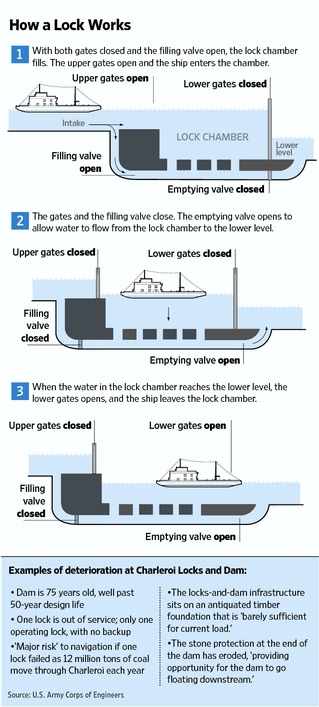

more. And 36% of the locks, which allow boats and barges to pass from

one water level to another along a river or a canal, are more than 70

years old.

On the busy Ohio River system, 2,500 miles of waterways that begin near

Pittsburgh and run to the Mississippi River, river haulers lost nearly

80,000 hours to lock outages in 2009, up from about 55,000 hours in

2005, according to the Corps. Some of the outages were planned, to

allow for repairs, but many were unplanned, the Corps said.

"Things could snap at any moment—that's what keeps you up at night,"

said Col. William Graham, commander of the Pittsburgh district for the

Corps. The failure of many locks at once would create an "economic

disaster," causing coal, grain fertilizer, and other goods shipped by

water to spike in price, he said.

Some 60% of U.S. grain exports and 20% of coal used for electricity

generation is moved by barge, according to Waterways Council, an

industry group.

In January 2010, for the second time in four months, a 51-year-old

section of a lock near Greenup, Ky., broke, delaying traffic on the

Ohio River. In December, Corps engineers in Washington state began a

prolonged shutdown of a worn lock on the Snake River and two on the

Columbia River.

Martin Hettel, manager of captive services at AEP River Operations of

Chesterfield, Mo., said a monthlong lock outage last fall on the Ohio

River created 72-hour delays in both directions, temporarily forcing

him to raise his hauling prices for coal to $3.70 per ton from $2.

"Somewhere down the line, the end user is going to pay for it," he said.

Waterways infrastructure is funded by both the barge and towing

industry and the federal government. The industry pays a fuel tax into

a trust fund for waterways construction, and the cost of projects is

generally split 50-50 with the government.

But many projects authorized for funds by Congress don't receive enough

federal money each year to remain on schedule, said Jeanine Hoey, a

chief of the Corps' engineering division. "If you are building a house,

and you buy a door one year, and next year you buy a garage door, and

the next a couple of windows—if you had bought the whole house together

it would have been much cheaper than buying each little piece at a

time," she said.

Piecemeal funding accounted for a third of cost overruns on projects,

according to a 2008 study by the Corps. The remaining two-thirds of

problems were design complications, some traced to the Corps' own

decisions, the study found.One project to repair locks at Paducah, Ky.

began in 1993, with a cost estimate of $775 million over seven years.

The still-unfinished project is now estimated to cost $2 billion and

won't be complete until around 2018. The Corps says the project has

been underfunded in all but five years.

Unpredictable funding has stymied the Charleroi Locks, which is part of

a project with an original $556 million price tag that has now

ballooned to nearly $1.5 billion, according to the Corps.

Some environmental groups are fighting the Obama administration's plan

to boost use of waterways to haul freight, arguing that it would

further harm already-polluted rivers. "The environmental impact to the

rivers involved has been quite devastating over a long period of time,"

said David Conrad, senior water-resources specialist at the National

Wildlife Federation.

River shippers, however, believe "the rivers are more pristine than

ever before, with the navigation industry adhering to safety and

environmental protection standards that exceed those required by

federal law or regulation," said Debra Colbert, spokeswoman for the

Waterways Council. "The fact is that transporting commodity freight via

our inland waterways is simply the most environmentally sound way to

move cargo," she added.

The barge and towing industry is lobbying members of the new Congress

to spend more on fixing locks and dams and overhauling the way the

government finances and oversees river projects.

A 20-year capital-development plan by the Inland Waterways Users Board,

which monitors use of the fuel tax, calls for the Corps to spend $7.6

billion to fix the lock-and-dam system over the next 20 years, with

both the industry and the government paying more.

The industry's fuel tax would rise from about 20 cents a gallon now to

between 26 cents and 29 cents a gallon, raising about $110 million a

year, compared with the current $85 million, according to the users

board.

Write to Jennifer Levitz at jennifer.levitz@wsj.com